The critics’ response to the world premiere of 4.48 Psychosis has been incredible. 4.48 Psychosis is my first finished opera, produced by the Royal Opera at the Lyric Theatre Hammersmith in April and May 2016. Here are some excerpts from the reviews:

The Independent. ★★★★★

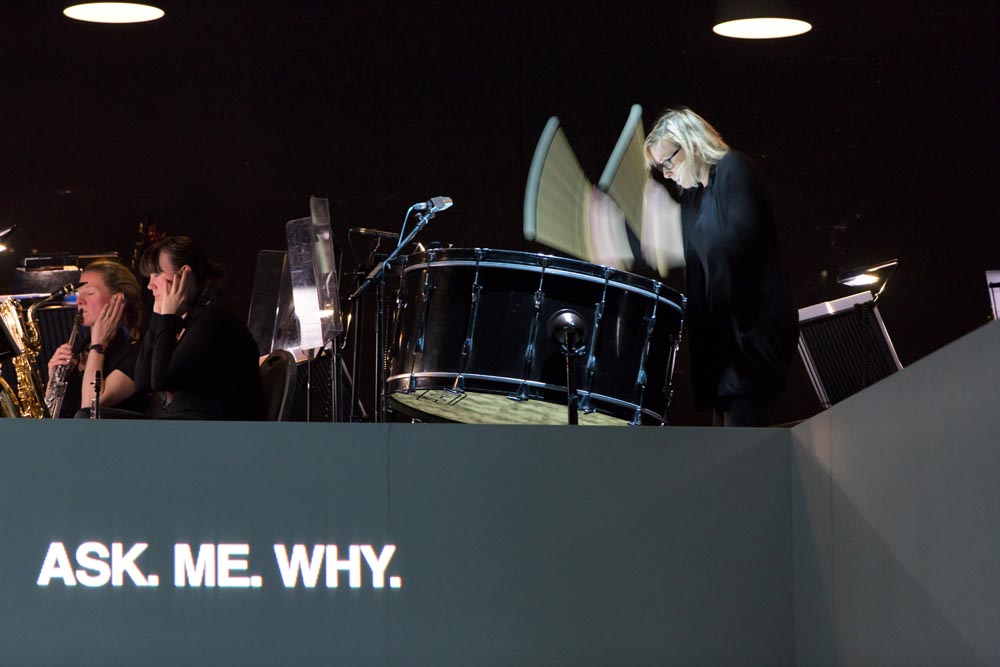

“Where this first-ever operatic setting by Royal Opera House Guildhall composer-in-residence Philip Venables succeeds is through simple honesty. With a score ranging guilelessly from motoric arrhythmia to wispy renaissance, director Ted Huffman and team attempt neither dramatic adornment nor explanation but allow the text to breathe within a kaleidoscope of inner-outer conflict. […] Duelling percussionists parley in a doctor-patient morse code. A tapestry of strings, accordion and saxes evoke polyphonies of yearning, while tenderly but inexorably we encounter hopeless recesses of the mind. Knowledge of Kane’s suicide shortly after writing the play can only make this humane and understated piece the more compelling.”

The Telegraph. ★★★★

4.48 Psychosis opera is rawly powerful and laceratingly honest. “Venables’s high-pitched score is a soundscape that imaginatively penetrates and dramatises the heart of this darkness. Ferocious peremptory drum beats mingle ironically with cocktail-hour smooch broadcast from the radio; the vocal writing veers between monotonous chant and shrieking anguish; and there are even moments of melancholy beauty, when the women harmonise laments for a lost life of beauty, friendship, value. […] This is an urgent message from black-dog hell, and it should not go unheeded.”

The Guardian. ★★★★

Philip Venables proves he’s one of the finest composers around with an intricate score inspired by Kane’s very personal story of clinical depression. “But the yearning, intricate vocal writing – Monteverdian in its timelessness – poignantly reminds us that depression is also the absence of love. Even in despair, Kane could be a savage ironist, and brassy, postmodern toccatas accompany the endless prescriptions of anti-depressants. The word “silence”was her only stage direction; Venables fills those pauses with distant muzak, among the most unnerving sounds in the work. […] above all, it confirms Philip Venables’s reputation as one of the finest of the younger generation of composers working today.”

The Times. ★★★★

Every self-harming syllable of Sarah Kane’s angry play is clear as Philip Venables finds a musical vocabulary for the drugs that treat depression. “Chroma’s strings, saxophones, accordion and synthesizer smear and blur in parallel to the drugs, sometimes delicately, sometimes violently. Click here for more info. Every self-harming syllable of the text is clear. There are neon-bright salutes to BartoÌk’s Bluebeard (a blast of Door Five C major), and a lament derived from the Agnus Dei of Bach’s B minor Mass.”

The Observer. ★★★★

Philip Venables makes Sarah Kane’s final work sing. “The revelation is how Venables has enriched her play through music. He challenges the conventions of opera. Via an array of resources he ambushes and refreshes an old art form. His technique is that of a collagist. Text is variously spoken, projected, amplified, conveyed rhythmically with percussion and sung, often in aria-like lament or chorale outburst. Snatches of Purcell – a mini viola fantasia arrests the action for several moments – and Bach coexist with high-energy funk reminiscent of the late Steve Martland. On reading later that Martland was Venables’s teacher, I can hear that element as a tribute rather than an imitation. I need to know more of Venables’s music to find his own musical identity: my task, not his.”

The Financial Times. ★★★★

‘Unhinged and chilling’. “Kane’s text is spoken, sung and projected on screens: it seems to emanate from everywhere. But Venables’ achievement is bigger than that. He manages to enhance Kane’s groundbreaking format with his own unbuttoned imagination. His score lurches between chattering polyphony, sounds of sawing wood, and post-romantic arias, spiced up with eerie violin shrieks. In the exchanges between patient and therapist, two percussionists thrash out rhythmic speech patterns as the text appears on screens beneath them. Then, when the din fades away, we’re left with the indifferent tinkle of elevator music. It’s unhinged and chilling, albeit laced with Kane’s trademark humour. Most of all, it is dizzyingly colourful.”

The Arts Desk. ★★★★

A musical dramatisation of Sarah Kane’s classic play finds both pain and consolation. “Picking his way through the chattering textual landscape with infinite care and understanding, cutting little text and adding none, Venables groups the material into genres. The structure that emerges is something like a sketch show; musical and dramatic tropes or textures return again and again, gaining weight and significance cumulatively through repetition and juxtaposition. […] Set against these fixed musical landmarks, stand-alone episodes make far greater impact. An exquisite aria for Clare Presland, sung over a synthesised accompaniment, is equal parts Purcell and pop song, a musical memory that offers a sustained moment of stillness, refusing to give way to the assault of other words and sounds. […] Venables’s orchestration (light on strings, heavy on saxophones and keyboards textures) is spare but telling, cultivating a mechanistic quality even when combining purely acoustic instruments that refuses to sentimentalise the outpourings of Kane’s speakers. Paired with the heady, giddy texture of so many upper voices, the result feels dangerously unanchored, unmoored from bass certainty and support.”

The Stage. ★★★★

“Philip Venables’ operatic version of Sarah Kane’s final play is both startling and immensely moving. […] a wide-ranging stylistic melange that counterpoints the freewheeling intellectual sophistication and through-the-floor psychological depths reached in Kane’s play.”

Music OMH. ★★★★

“Venables’ score, played by the CHROMA Ensemble conducted by Richard Baker, is poignant and atmospheric and suits the words very well. It allows some to be uttered slowly, and others to be rattled through in a haze, signifying how someone’s thoughts can rush in and pile on top of each other. While this 4.48 Psychosis undoubtedly constitutes an opera, the music is best understood as a contributory component to a sensory experience that is also created through word, setting, gesture, movement and sound in the widest sense of the word. We sometimes hear the radio play or ‘voiceovers’ from offstage. Similarly, ‘arias’, cries of despair or religious sounding music can be abruptly interrupted by other sounds, revealing how thought patterns can shift and some feelings drown out others.”

The Spectator.

“Experimentation in the service of absolute emotional precision: Venables’ economical work is one of the most exhilarating operas in years, even while it gives voice to some of the darkest thoughts imaginable.”

Tempo Journal

“I cannot recall having been as powerfully moved by an opera as this, much of it watched with my hand clasped over my mouth.”

Bachtrack.

Powerful and assured. “Whenever the music made use of multiple layers, and particularly when these materials were somehow archetypal or reminiscent of other music, Venables’ clarity of conception as a composer really shone through. From lullabies through sad electric keyboard pop songs to the descending bass of Baroque laments that surfaced repeatedly, these musics were always tending towards the past; towards memory, and in connecting with our own memories of them, lent depth and empathy to the ‘character’ presenting them. […] Seeing a list of the formal devices used by Venables, it would be easy to think that these were used as crutches. But Venables’ opera is a very assured and crafted work, placing Kane’s words in a formalised and estranged context which manages not to make the emotions overwrought, but not downplaying them either.”

British Medical Journal.

“The shimmering score, the choreographed moves of the singers, and the (often projected) words work well together, in verses and prose, staccato rhythms, and rich polyphonic sounds. During moments of “silence,”lighter music (muzak?)—probably recorded—was playing in the background, making me wonder whether this was somehow happening in the main character’s mind. Or maybe in my own mind? The production was incredibly tense, and every crisis that the protagonist experienced seemed worse than the preceding one, her sense of isolation, anger, and hopelessness more acute, her withdrawal into her despair more final. She sings about a previous suicide attempt by taking an overdose of her multifarious medications; this had been unsuccessful. […] It felt difficult to applaud after such an unremittingly bleak 90 minutes, but the performances and staging had been absolutely superb. The operatic format was an absolutely inspired choice as the words were rhythmical and music can convey emotions that words cannot, or convey them differently. Outstanding!”